For the past few weeks Fremantle, our “other home” and the port city for Perth in Western Australia, has been central to a global debate on the role played by cruise ships in the spread of COVID-19. Put simply, as Indian Ocean, Asian and other ports closed up, Fremantle became a natural destination. Within days of the pandemic being declared, ships from several lines turned up. https://fremantleshippingnews.com.au/shipping-news/

For the past few weeks Fremantle, our “other home” and the port city for Perth in Western Australia, has been central to a global debate on the role played by cruise ships in the spread of COVID-19. Put simply, as Indian Ocean, Asian and other ports closed up, Fremantle became a natural destination. Within days of the pandemic being declared, ships from several lines turned up. https://fremantleshippingnews.com.au/shipping-news/

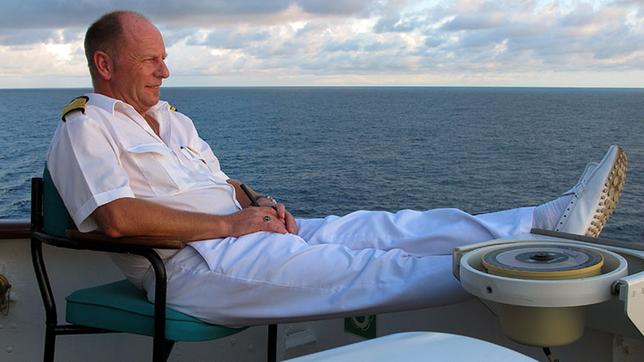

Now, during recent years Sandi and I have spent a fair time on such ships where I have been a fortunately invited lecturer, a wonderful experience. Just one of the benefits is a range of now firm friends met during the course of those lectures. Another is the vast range of fascinating people met including senior military and intelligence figures, judges on international tribunals, successful businesspeople and academics, philanthropists and all the rest. On our very first voyage, my final lectures into Capetown were cancelled to make way for… Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

That ship was commanded by Captain Jonathan Mercer. Ironically, it concluded its most recent journey at Fremantle, again commanded by Captain Mercer on his last hurrah. It began as a round-the-world voyage but is now heading towards South Africa en route home, almost all of its passengers having been flown out of Perth.

For a terrific sense of the cruising world and what has been happening, check Captain Mercer’s fascinating blog in which he particularly mentions that Fremantle stop. http://captainjonathan.com/fremantle-and-the-end-of-the-world/ He is too much the diplomat to mention all the wider drama, not so much with his ship as with those others that hove into Fremantle with confirmed cases of COVID-19 aboard.

Principal among those is the Artania, now central to a diplomatic and political as well as public health storm.

Briefly, WA Premier Mark McGowan had initiated tough anti-virus measures and was alarmed by the prospect of these ships disgorging passengers among the general populace.

That was understandable, given the developing fiasco around Sydney’s Ruby Princess story where local health officials allowed about 2,700 passengers out into the general populace even though COVID-19 had been identified aboard. That so far has led to 440 identified cases and five deaths across Australia. https://www.news.com.au/travel/travel-updates/health-safety/coronavirus-ruby-princess-mistake-caused-infection-cases-to-explode/news-story/c79dcc2c83704d53b6ecd8e5b0ce7e59

[Note – some links may have paywalls]

So McGowan declared bluntly that Artania, in particular, would not be allowed to land, even though public knowledge had it that there were some very sick people aboard. https://thewest.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-mv-artania-msc-magnifica-and-vasco-de-gama-everything-you-need-to-know-about-was-troubled-ships-ng-b881499462z

McGowan’s navy lawyer background before becoming a politician made this stand puzzling – maritime law and lore alike prizes life and safety at sea, as does common humanitarian principle. He seemed scarcely likely to win that one. Sure enough, the ship did dock, the sick went to hospital, as many others as possible were convoyed in exclusion to the airport and put on three planes back to Germany chartered by the cruise company.

But that was not the end of it. Some passengers remained and so did the crew, many of whom were now displaying signs of the illness. The nature of general and cabin crew staff on cruise lines is a major subject in itself, but suffice to say that for a very long time most have come from places like Indonesia and the Philippines, for a host of complex reasons. (this link is a little old but gives the background) – https://www.tipsfortravellers.com/revealing-the-secret-behind-the-crew-composition-on-holland-america-line/

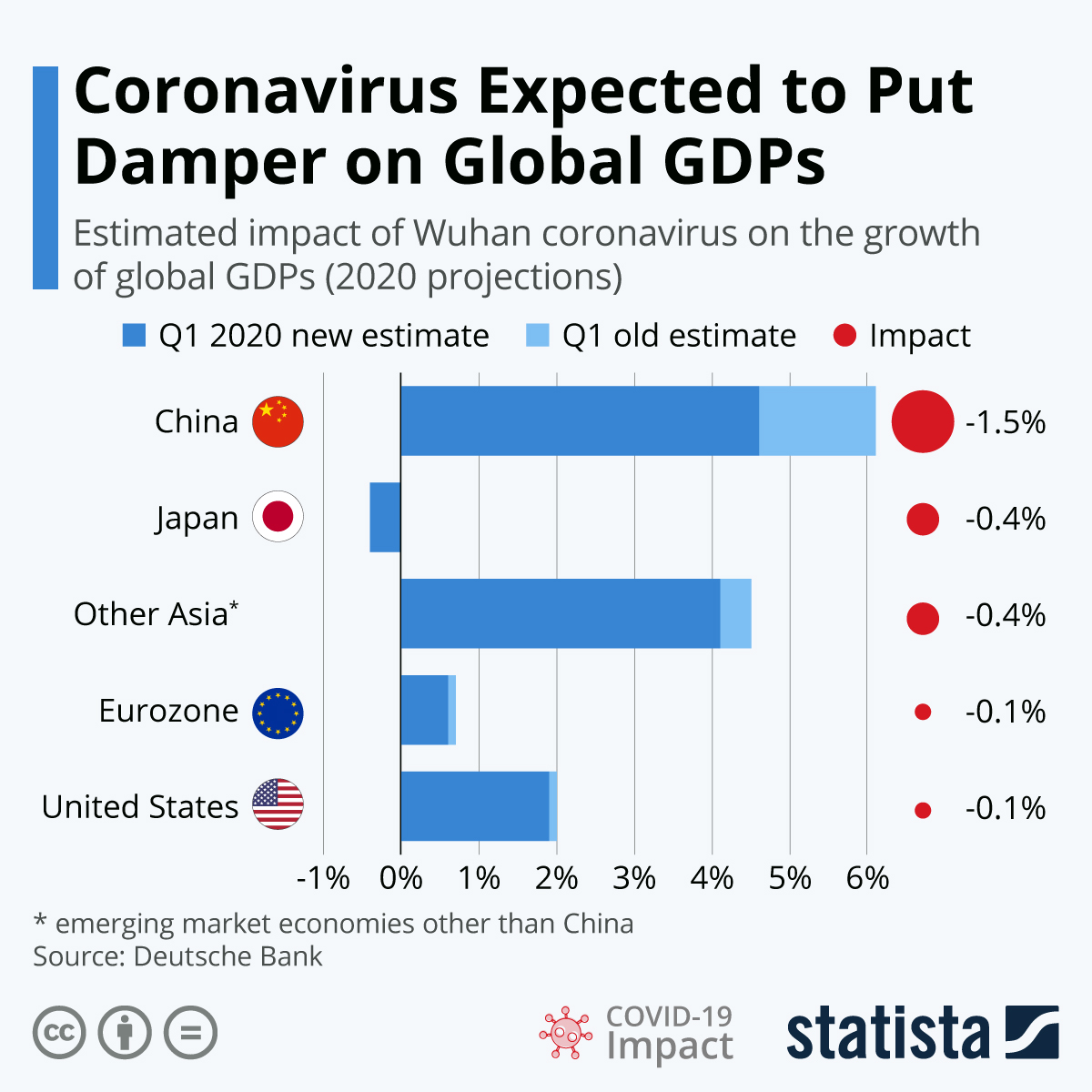

As a sidebar, one major knock-on effect of what is happening now is the severe economic and financial jolt those countries will feel as a result of the disruption in cruise activity.

So, McGowan was again adamant the Artania must leave and there were wild reports about Border Force being ordered to get the ship out, that the navy would get involved and so on. https://thewest.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-wa-premier-mark-mcgowan-wants-covid-19-hit-cruise-ship-artania-gone-ng-b881507578z

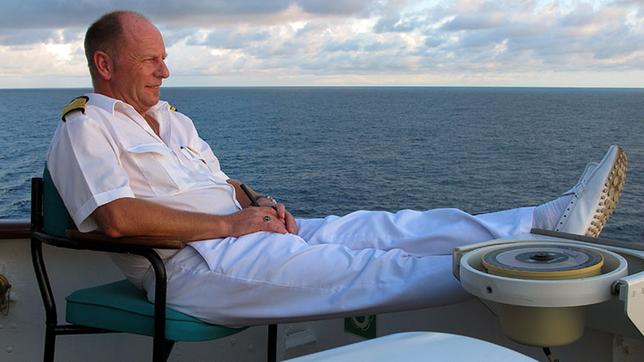

A vigorous behind the scenes negotiation was made all the more interesting by the presence of Captain Mercer’s Artania counterpart, Captain Morten Hansen. It turned out he has 30,000 Facebook followers, courtesy of his starring role in a European reality television show focused on the cruise industry. https://www.facebook.com/Kapitän-Morten-Hansen-Fanseite-178359965533287/

The West Australian, the state’s rag of no other choice, thought this “Bizarre”, to quote the header: https://thewest.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-artania-cruise-ship-captain-morten-hansens-bizarre-background-revealed-ng-b881506884z

At the time of writing, the Artania is still at dock a few hundred metres away, according to my Marine Traffic app, and still carrying the signs of gratitude hoisted by passengers and crew, obviously not directed at the Premier.

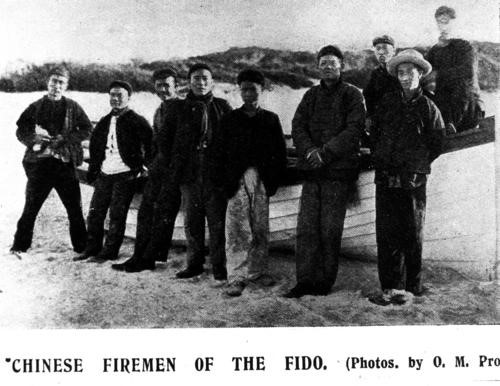

We might note here that Australia has long had a problem with ships, especially those coming from Asia. Back in 1880, for example, as the first planks were laid in what at Federation became the White Australia policy, ships were restricted to bringing in one Chinese person per 500 tons of gross tonnage. And those ships were not of the 45,000 tonnes type that is the Artania.

At the same time, Australian authorities were incensed to discover that, apparently, the British in Hong Kong had been exporting criminals quietly by putting them on ships to Australia! That, of course, was how Australia was founded in the first place. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/900945?searchTerm=Chinese%20banned%20from%20landing%20in%20Australia&searchLimits=sortby=dateAsc|||l-category=Article|||l-decade=188 A hundred or so years later, Australia began turning back the refugee boats and that remains the policy now on both major sides of politics in the country.

Across the world from the Artania, however, an even bigger standoff was developing.

A couple of days before the pandemic was declared, the Zaandam set off on a cruise from Buenos Aires that was to finish in Chile a couple of weeks later. But COVID-19 appeared on the ship. The pandemic now declared, several cities closed their ports and the ship had to head for home, Fort Lauderdale in Florida. News reports appeared of people onboard having died from the virus and with others sick.

The Zaandam was met off Panama by sister ship, the Rotterdam (on which Sandi and I have been) that had sailed from San Diego with extra medical staff and supplies and no passengers. Large number of passengers were then transferred to the Rotterdam by tender – that means the ships lifeboats being used to transport passengers, as often happens at ports where the ships are too big to dock. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/01/us/holland-america-zaandam-cruise-ship-florida/index.html

This is the point at which those who have experienced cruising will start to appreciate the tension on board. Several planned itinerary stops have been cancelled, news spreads that sickness has emerged and, importantly, it is unclear what might happen next. For several days, this had been and remained the state of play on board. Rumours spread. People are confined to cabins – and on these ships an “inside” cabin is cheaper, but it means no windows. So being confined takes on an extra dimension. Friends and family are calling in wherever possible, the internet conveys messages, more theories appear. Then a large transfer of passengers takes place. The mood on board can be imagined. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/the-holiday-of-a-lifetime-an-oral-history-of-the-infected-rejected-zaandam-cruise-ship/2020/04/02/958c2288-7491-11ea-87da-77a8136c1a6d_story.html

The view developed on board, it appears, that “sick” and “healthy” ships were being established and that, clearly, upset a lot of passengers. That was effectively the reason the President of the line made a videoed statement into both ships to explain exactly what was going on and why. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=586897791900229&external_log_id=863dd1ebb3ceabed6a4c11954ae727e3&q=holland%20america%20zaandam

Both ships were eventually cleared to transit the Panama Canal, at which time those in charge faced another emerging problem.

Like Premier Mark McGowan in Western Australia, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida had also been a navy lawyer officer, in the US Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps, and had been deployed to Iraq. And like McGowan, he did not want these ships in Florida. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/holland-american-coronavirus-covid-19-zaandam-rotterdam-2020-3

But also like McGowan, DeSantis had to allow the ships to dock (on 2 April) and for the same humanitarian reasons as allowed for by his fellow Republican, President Donald Trump. http://www.sun-sentinel.com/opinion/editorials/fl-op-edit-zaandam-cuise-ship-20200401-3cmfs42c4zep7d6rkux4utfqbi-story.html?fbclid=IwAR23f2Qyp0-37IA90o9kSfcSDek5DlNJmeYjLH008ZcEAFAQEQw1sz6PWaI

Both episodes demonstrate the resurgent localism that has emerged in wake of COVID-19, what some see as a retreat from globalism.

As those ships reached Fort Lauderdale, for example, McGowan was turning Western Australia into an “island within an island”, as he terms it, with a “hard border” being declared against (and I use that word deliberately) the rest of Australia. https://thewest.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-premier-mark-mcgowan-announces-hard-border-closure-for-wa-ng-b881508092z It is not that long ago that a “hard border” in Ireland was the pivotal matter in BREXIT.

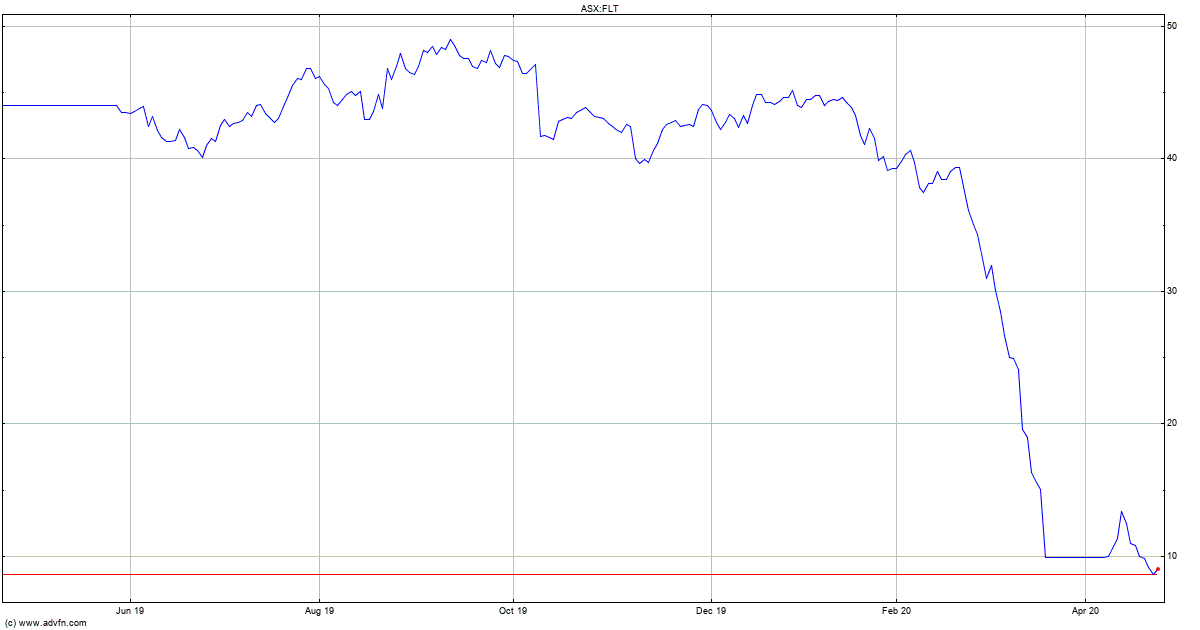

By the time the two ships did dock in Florida despite DeSantis’s original view, their parent company was displaying the bigger consequences in all this, remembering that these were not the only ships facing trouble around the world. https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/cruise-ships-still-sailing/index.html

Carnival Corporation controls at least half of the global cruise line business, operating under several flags. https://www.carnivalcorp.com/ Obviously, the need to stop cruising has enormous financial consequences, and that was signalled by the corporation’s need to raise $US6 billion in additional funding. At a rough operating cost of $1 billion per month, that allows six months for things to turn right under the current arrangements. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/carnival-corp-secures-rescue-financing-package-on-wednesday-to-help-the-embattled-cruise-ship-operator-navigate-choppy-waters-in-the-months-ahead-2020-04-01

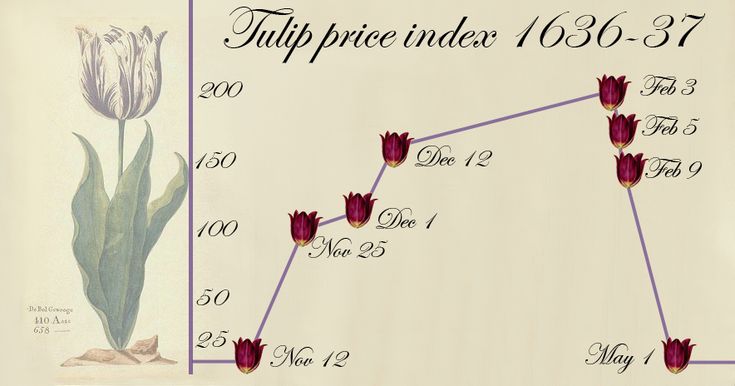

At this point, though, “turning right” will almost certainly involve major change, and in that sense the cruise industry becomes something of a touchstone for the world as a whole when it comes to what happens next. Change is inevitable.

Traditional long distance cruising demographics, for example, coincide with the groups most vulnerable to COVID-19, the over-60s and especially the over-70s. After all this, that demographic might be a bit reluctant to sail as much if at all and, in all truth, most if not all cruise lines had been trying to diversify away from a reliance on that demographic anyway.

Then, how many ports and cities will reopen to this travel anyway? And that goes for the tourism industry as a whole. Before this, places like Venice and Amsterdam had already begun shutting out big cruise ships, and they are now likely to be joined by others. https://www.malaymail.com/news/life/2019/08/02/venice-calls-european-port-cities-to-arms-over-cruise-ships/1776848

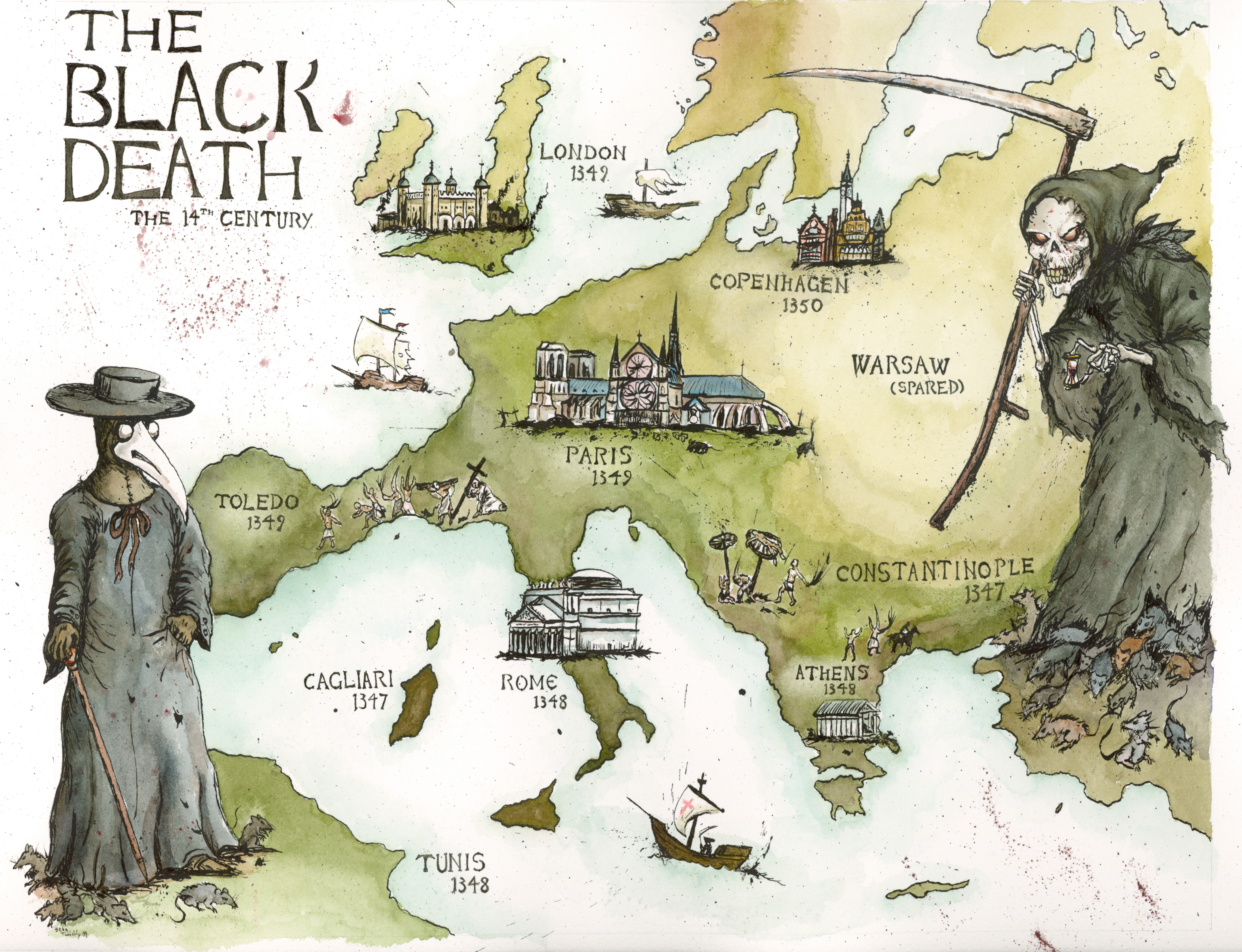

Another isolation effect is to turn us medieval. Back then, villagers scarcely ventured outside a ten to fifteen mile radius ever in their lifetime. It feels a lot like that now, and if the isolation against COVID-19 continues for several months, some of those effects will likely continue.

And if we do want to cruise, how do we get to ports of departure unless, like us, the terminal is just up the road? Who will fly us there? Virgin Australia needs a massive Government bailout to survive, and Air New Zealand has signalled it will be a domestic carrier only for some time to come. https://australianaviation.com.au/2020/03/breaking-air-new-zealand-reduces-long-haul-capacity-85/

Will the confidence to travel return? In some, like the young, of course, but while some tourism experts confidently expect a big bounce back, others reckon it will take the mass tourism of recent times a long time to return. https://www.eturbonews.com/542449/coronavirus-is-the-travel-tourism-industry-lost/

For Carnival, some of its flags might well disappear. Even if they do not, the business will change and, like everything else at present, it is not immediately clear what that change will look like.

But for the moment, the Artania still sits up the road here in Fremantle with more crew COVID-19 sufferers being taken off, a symbol of the havoc wrought upon us by this virus that will go down as one of those significant historical agents of change.

For the past few weeks Fremantle, our “other home” and the port city for Perth in Western Australia, has been central to a global debate on the role played by cruise ships in the spread of COVID-19. Put simply, as Indian Ocean, Asian and other ports closed up, Fremantle became a natural destination. Within days of the pandemic being declared, ships from several lines turned up.

For the past few weeks Fremantle, our “other home” and the port city for Perth in Western Australia, has been central to a global debate on the role played by cruise ships in the spread of COVID-19. Put simply, as Indian Ocean, Asian and other ports closed up, Fremantle became a natural destination. Within days of the pandemic being declared, ships from several lines turned up.