As any writer will tell you, the appearance of a new book or even a new edition is a special moment. All the years of research, experimentation, false starts, editing, doubt, desperation and even anxiety suddenly become worthwhile – at least until the anxious anticipation of reviews sets in.

But those same writers might also admit that, if they have produced a few works, some are more special than others.

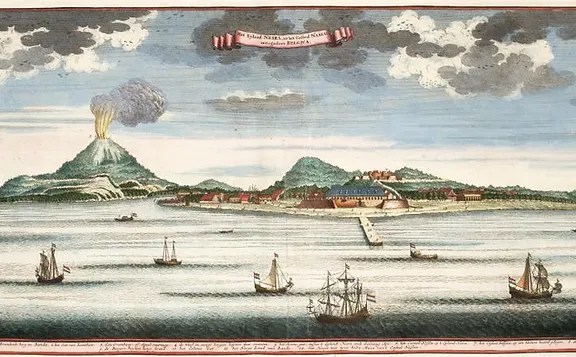

That is the case for me with Playing the Game: How Cricket Made Barbados which, as a social history, explains how the game’s organisation there enshrined colour, class and status as the determinants of societal relationships in the ongoing and still persistent aftermath of slavery. The island became one of the world’s best production lines of great players, but many of them had to fight hard to escape those tight social strictures and, indeed, many more potentially great players were defeated by the barriers they encountered.

As a simple historian the task was straightforward enough: do all the broader history and more specific cricket archival research to create the story and analytical lines.

Researchers all have archival horror stories, usually about disappeared sources or difficult archivists, sometimes a combination of both. There are often lighter moments, though. Years ago I was lucky enough to interview the wonderful George Rude, author of The Crowd in the French Revolution and an originator of the “history from below” approach by examining all the court records of arrested rioters. https://amzn.to/4k7JcTP He had a marvellous story about being locked overnight inside the main French archive with that other equally wonderful historian of France, Richard Cobb.

There was precious little chance of being locked inside the Barbados Archives, with all the records looked after meticulously by the lovely staff members who were always as helpful as possible to the usually very few researchers. Once home for the unfortunate Barbadian victims of leprosy, the archives now sit just down the hill from the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies, with occasional breaks from reading taken on the outside verandahs yielding glimpses of the fabled Caribbean. Sadly, a major fire during 2024 destroyed many invaluable documents.

The cricket archives proved more elusive but I was able to access the Barbadian Cricket Association records while the marvellous Edith Kidney opened her family’s invaluable cricket collection.

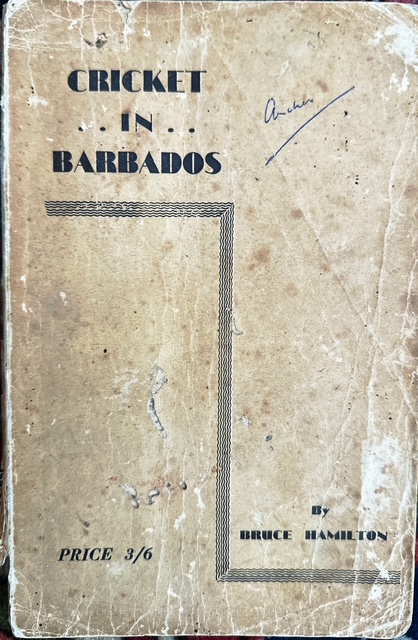

And the wider hunt for material was motivating. A major source of early Bajan cricket detail is Bruce Hamilton’s 1947 Cricket in Barbados and, as always, the polymathic Gideon Haigh provides a great back story because Hamilton, brother to writer Patrick Hamilton, was a devoted Marxist all the while teaching at an elite school in the ever conservative Barbados. The book itself is scarce and normally expensive, but I found a copy in Barbados in a nondescript collection of books amidst the junk of a general store. Some internal notes suggest it belonged originally to “Shell” Harris, a notable cricketer, teacher and later sports commentator who appears in a lovely Herman Griffith-related story at p.45 of my book.

Stimulating though it all was, that alone did not spark this into one of those “favourite” books. Rather, that came from the place, its people and their combined impact on Sandi and me, especially through the lived cricket experience in contrast to the learned ones.

As I explain in the book, we engineered a year on half pay so I could play what turned out to be my last competitive year of cricket in Barbados which pegged its currency against the $US at precisely the time Australia’s just-floated dollar sank dramatically. Slim Pickens was not just the name of an actor that year. And selecting a team for which to play involved far more than mere cricketing ability, given the game’s socially constructed past. But my choice turned out to be a wonderful one as around the island I became known as “the white man playing for Maple”. That opened far more doors for us than if I had played elsewhere, at the historically white elite club, for example.

Playing the game there involved my becoming as much anthropologist and sociologist as historian, something I had done to a degree in my work on south India but never to this extent and with this sort of cumulative effect. I was living the game as well as playing and studying it, and most of the people I dealt with in Barbados thought, no, knew that was a crucial step in understanding how the island came to be the way it was and remains.

So every day became as much an exploration as a study of Barbadian social needs. A few years later Greg Dening at the University of Melbourne invited me to his “Histories in Cultural Systems” seminar where the great Chicago anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (a Cubs baseball fan) spoke to a history of human needs. In Barbados, cricket met much of the human need for social and psychological comfort and space as sport does more generally across a large swathe of the world. We experienced that at first hand in Barbados and, for me at least, that is a strong thread throughout the book.

Cricket there, and sport more generally, then, provides and important social service not met by other forms of activity, and capturing that has been a major target.

Interestingly, my other “favourite” book does much the same, and for similar reasons. I spent most of 2010 working in Syria and left as the recently concluded war was just emerging in all its awfulness. A House in Damascus: Before the Fall chronicles my lived experience of being in the magical Old City and remembering all the historical characters who experienced the people, practices and panoramas that I did and still remember with great affection.

In creating that “favourite” Barbados cricket book, there was also an extended learning curve provided by other writers. Prime among them, of course, was CLR James’s extraordinary Beyond A Boundary , still among the greatest of sports books even if most readers still struggle to see it as such. https://amzn.to/44dJ5jI I read it first when I was seventeen and understood little if anything it said. Much of my longer term sports story has been gaining that understanding.

A later and more accessible “must read” was Michael Manley’s A History of West Indies Cricket. https://amzn.to/4k7JcTP Here was the socialist Prime Minister of Jamaica putting cricket firmly in the frame alongside the cause of Caribbean nationalism and self-determination. He might have been less erudite than, say, the eminent Harvard sociologist and fellow Jamaican Orlando Patterson who also wrote on cricket in the same vein, but with a far wider impact.

Another early read in that journey was Roger Kahn’s The Boys of Summer, the story of the Dodgers’ 195 World Series win with the headline act being Jacky Robinson, the first man to beat the colour bar in the major leagues. https://amzn.to/4k7mgnN A marvellous piece of writing in its own right, it also made me realise that the importance of sport was not contained nationally, culturally or any other way. Modern sports dictate much of modern life.

Add traditional life to that, too, as with Clifford Geertz on the Balinese cockfight, best seen in his The Interpretation of Cultures. https://amzn.to/4nedPcO His insights there along with my own experiences in India and elsewhere sharpened my focus on Asian sports like sumo which, marvellously, is now explained socially in The Way of Salt by my Tokyo-based Australian friend, Ash Warren. https://amzn.to/3G8n4uv

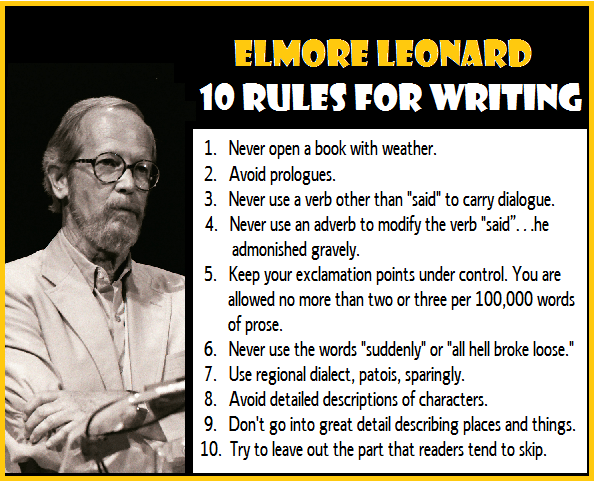

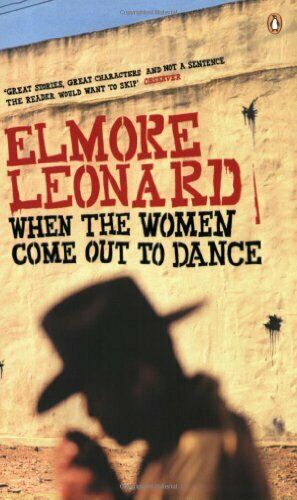

If this all seems too learned, then I have worked hard to make these often complex ideas readable and accessible, and that means learning from great writers. There are probably far too few writers of academic bent turning to Elmore Leonard for literary inspiration, but I do because the principle is that if you can keep them reading you will keep them learning – Clifford Geertz meets Raylan Givens, as it were, with Leonard’s Raylan a wonderful introduction. https://amzn.to/44pWne1 And Justified, the television version of those stories starring Timothy Olyphant and Walton Goggins, might just be at the top of my all-time favourites.

I can make the same “learning from writers” point with crime fictionistas like Michael Connelly, Kate Atkinson, Michael Dibden, Patricia Highsmith and all the rest.

At present I am catching up on the novels of David Nicholls, one of those lovely, clever writers who use of language captures the human spirit and quirkiness with ease and accuracy, as seen in his most recent one, You Are Here. https://amzn.to/43Wsdis His individuals are memorable and make the point about the social whole, when too often as historians we try to work that in reverse, for the most part unsuccessfully.

Here, though, I am also influenced more recently by my journey into family history. As historians we often pontificate about what people did and why. When it comes to your “own” people, however, there is an increased need to “understand” better what often appear as to be harsh, unkind or even treacherous actions. In writing Barbados, then, I have been as mindful as possible in trying to think about the individuals inside this big collective.

I hope you enjoy the experience of reading the story, then, it has certainly given and still gives me the thrill and pleasure of having been there to put it together.

Note: I may receive a small Amazon commission for any orders lodged from links here