In a recent and wonderful Times Literary Supplement piece, the prolific English writer and long-time Italian resident, Tim Parks, added Boccaccio (of Decameron fame) and Giovanni Villani (the fourteenth century Florence banker and chronicler) as Black Death diarists whose notes bear current relevance. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/milan-coronavirus-italy-tim-parks-essay/

(If you love Italy you must read Tim Parks: Italian Neighbours; An Italian Education; Italian Ways; and my special favourite A Season With Verona).

Like many others, I had started with Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year that recorded the English effects, but as Tim Parks rightly reminds us, the Black Death changed lives throughout the-then known world, and the themes of that time resonate now.

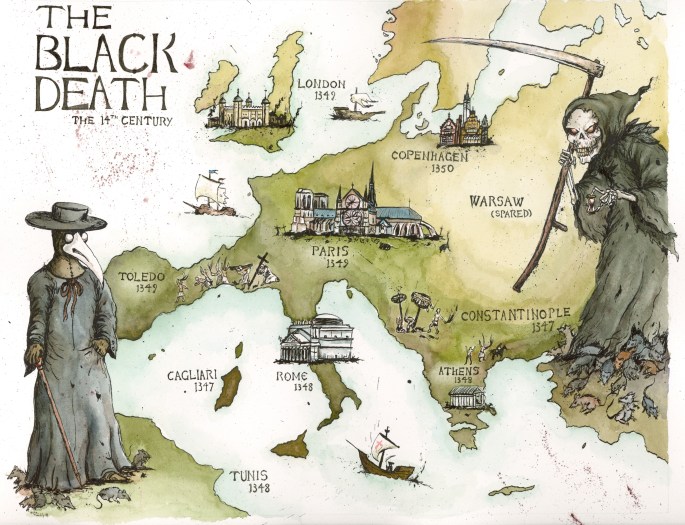

It is widely accepted, for example, that the plague “arrived” in Europe at Messina, in Sicily, on twelve trading ships come from the Black Sea in October 1347. Many of the seaman were already dead, exhibiting all the terrible signs of what became known as the Black Death. From there the “pestilence” spread throughout Europe killing millions, decimating towns like Florence.

Sitting here now in Fremantle, Western Australia, nearly seven hundred years later, the helicopter noise I hear is sparked by the presence of some modern cruise ships that have become the successors of the dozen that reached Messina. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-28/cruise-ships-present-a-perfect-coronavirus-storm-of-problems/12093768

The culprit de jour is the Artania which, my MarineTraffic app tells me, is a 44,000 tonne ship built way back in 1984 (thank you, George Orwell), 230 metres long and registered in the Bahamas.

But the “Grand Lady” or the Queen of the Line in some descriptions, is even more interesting than that. She was launched in 1984 by Princess Diana and named, appropriately, Royal Princess as part of the Princess Line fleet in which she sailed until 2005 when transferred to P&O. In 2011 she was sold and then chartered by the Phoenix Reisen travel conglomerate and shipping line in Germany. Artania carries about 1200 passengers and almost 600 crew.

Back in December 2019 she left Hamburg on a 140 day round-the-world trip down the West African coast then out into the Indian Ocean, across to Southeast Asia, down the Australian East Coast, onto New Zealand then across to South America, up to the Caribbean, the USA and Canada before heading home to Germany. That cruise was due to end this May and for many aboard, would have been the trip of a lifetime.

But that timeline put it right across the trajectory of COVID-19.

Inevitably, its journey was altered. According to some passenger accounts, at least, that had started in Singapore and Indonesia by February 2020. https://www.translatetheweb.com/?from=de&to=en&ref=SERP&dl=en&rr=UC&a=https%3a%2f%2fwww.schiffe-und-kreuzfahrten.de%2fnews%2fcoronavirus-ms-artania-auf-abwegen-in-asien-waehrend-ihrer-weltreise%2f198473%2f Ports were closing daily because of the virus threat, so the ship made for Australia, where things were also getting grim. On March 14 the company cancelled the cruise and Artania was set for a non-stop “crossing” to Bremerhaven, with any passengers not wanting to do that to be flown home to from Sydney.

Then came the Ruby Princess incident in Sydney where passengers who had returned positive COVID-19 tests were somehow allowed to wander off at large, setting off a major chain reaction.

The Princess line, of which Artania was once part, already had a troubled role in this global panic. During February, when Artania was around Singapore, the Diamond Princess was stuck in Japan with multiple COVID-19 cases and a major challenge on how to proceed. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/06/inside-the-cruise-ship-that-became-a-coronavirus-breeding-ground-diamond-princess

This resonated especially in Perth, Western Australia – James Kwan, the state’s and Australia’s first COVID-19 fatality, on 1 March 2020, was a well-known local tourism figure, and had been evacuated from the Diamond Princess. Since then, cruise ships had figured prominently in dispatches.

That demonisation was understandable, but not necessarily logical. The argument was that hundreds and thousands of people were cocooned on these ships that became, in popular parlance, “petri dishes” for the virus. That is true to an extent. But the New Zealand story here is interesting – health authorities there publish details of all positive cases, and a huge percentage are directly connected with air travel. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120577713/coronavirus-66-south-island-covid19-cases-confirmed

Ships are much easier to demonise than aeroplanes, it seems – although both now face troubled futures. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/covid-19-puts-travel-industry-in-a-perfect-storm-of-chaos/

Like those Messina ships, Artania was a pariah by the time it arrived off Fremantle, rumoured to have up to seventy COVID-19 cases aboard. WA Premier Mark McGowan (a former navy lawyer) argued trenchantly that the ship was a Federal responsibility so the sick should be taken care of in defence facilities and the rest not allowed to land. https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-wa-premier-mark-mcgowans-solution-for-covid-19-cruise-passengers-off-fremantle-ng-b881500431z The local Australian Medical Association branch was already concerned at the state’s lack of pandemic preparedness and considered Artania’s arrival as a looming disaster.

That was reinforced by the arrival of the Magnifica with more COVID-19 cases, the imminent arrival of the Vasco de Gama (most of whose passengers will now quarantine for fourteen days on the local tourist island of Rottnest, named originally Rats Nest in 1696 by Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh who failed to identify the marsupial quokka) and recent visits from other diverted cruises.

While the Premier had eventually to compromise, Twitter and Facebook commentators went way further: “send them packing, back where they belong” and worse, far worse, characterised the public response. Just the odd humanitarian voice thought the sick needed care.

That was a direct offshoot of the now-well known pandemic panic that saw supermarket shelves stripped of toilet paper and hardware stores of generators and methylated spirits. https://thewest.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-panic-buying-chaos-as-wa-shoppers-turn-violent-ng-b881489862z

As with the Black Death, it was everyone for themselves.

And this was just three or four weeks after local opinion had been that more cruise ships operating out of Fremantle as a result of port disruptions like those suffered by Artania would be a great boost to a fragile state economy.

This was another demonstration of just how rapidly COVID-19 was reframing daily life and, as at Messina, what had seemed like a good thing was now decidedly something else.

The Fremantle story also saw the continuation of another theme present in Messina.

Many if not most Black Death accounts laid responsibility for the origins of the disease with “Asia”. More recent accounts place its rise around 1320 in the Kyrgystan/Mongolia region. The spread was then said to be through China and India and on into Europe.

It is readily apparent that the current slanging match led by President Trump blames China for the rise of COVID-19. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/03/trump-calling-coronavirus-chinese-virus.html That rhetoric further excoriates China for then having the temerity to offer assistance to subsequently afflicted countries.

Much conservative Australian commentary mimics this. Organisations like the Australian Strategic Policy Institute – that claims to be “independent and non-partisan” (but was set up by a John Howard conservative government and remains part-funded by the Department of Defence) – serves up a constant China-bashing line, as in this from its Director: http://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/letting-beijing-bully-know-our-neighbourhood ASPI staff figure prominently in the The Australian that has adopted an aggressively anti-Chinese stance on just about everything – an ex-Australian journalist produced this on the virus: https://www.news.com.au/world/asia/how-chinese-president-xi-jinping-failed-to-manage-the-coronavirus-outbreak/news-story/1a06e142ed15bf4124a95b1c3f4533e7

Now, this present viral strain did appear first in Wuhan, and China originally did struggle to deal with it and now seems to be in control – even if critics like Fernando argue that we cannot trust the data coming from China. That suggests we can trust the data coming from the United States or from Australia for that matter, and many of us would hesitate to go that far.

Right now, as with so many international matters, focus should be on cure rather than cause, and on the ways in which a global community can collaborate to combat this problem, not to mention the rapidly escalating financial and economic one which is following.

It is useful here to caution against immediate attribution of blame, as the Black Death case again indicates.

Almost every European account of that catastrophe suggests, as noted earlier, that China and India “were to blame”. Yet as Laksmikanthan Anandavalli pointed out a few years ago (in one lovely essay among several others on plague in Tangents), there is a problem here. No major account of India at that time (including the great work by that inveterate Arab traveller, Ibn Battutah) details anything like the Black Death. Yes, there were outbreaks of pestilence – but none exhibited the tell-tale symptoms of that scourge. https://mla.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj1421/f/tangents07.pdf

What this points to, of course, is the way in which assertions transform into accepted fact, and the need to revisit those assertions – and we are all guilty of the first at some point, and delinquent on the second too often! (Everyone who has got to this point will now go off factchecking, so apologies in advance for any discrepancies.)

The Black Death changed the-then known world for generations, and signs are this present “pestilence” will do the same. Cruise ships and airlines are under immense financial pressure, the tourism industry will likely change dramatically. It was already challenged, with cruise ships shut out of places like Amsterdam and Venice (which suffered so massively back in the fourteenth century).

Our borders will not be so open again for a very long time. We may see limits on essential services goods last longer than we think. Many banks are reluctant to accept actual cash, hastening electronic commerce that will lead to further social inequality. As universities and learning institutions go fully online, will we ever get students back into lecture halls and classrooms? Will we ever again work in large open-plan environments, or even in the same building? Perhaps we will be the twenty first century version of The Lonely Crowd? https://university-discoveries.com/“the-lonely-crowd”

But to return to Tim Parks – the other important question may well be who becomes the great chronicler of all this, someone from whom the future might learn as we learn from Boccaccio and Ibn Battutah, Defoe and Villani? Who will chronicle the modern plague ships? It is a fascinating story.